Quality ingredients often come with a story, and VERJUS is no different. I have been on a bit of a focused "Verjus Kick" for the past year, tasting Verjus all over Europe and North America.

Quality ingredients often come with a story, and VERJUS is no different. I have been on a bit of a focused "Verjus Kick" for the past year, tasting Verjus all over Europe and North America.

Before the story, a simple question: “What the Heck is Verjus & how do I use it?”

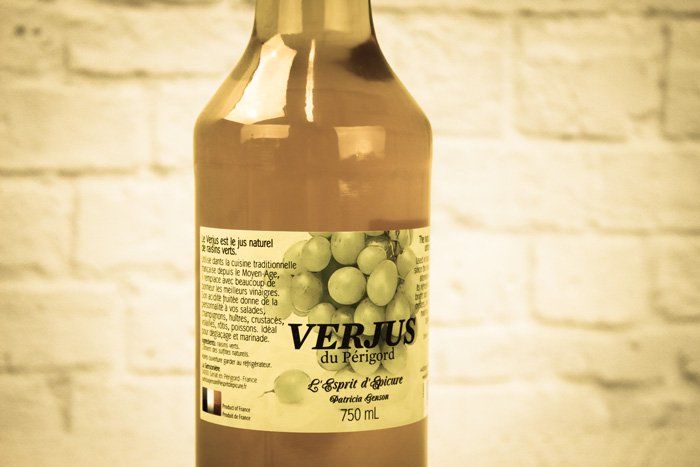

Verjus which translates roughly from old French (aka ‘middle French’) as “Green Juice”. Verjus is simply the fresh juice from green, unripened grapes.

You know … the grapes when unripe that are so tart and acidic that it makes you wince when you taste them?

The origin of Verjus is well documented in French cuisine but the cultural beauty of Verjus is the rich tradition of its use across the Middle East in Persian and Syrian Cuisine. You can read about the cultural swath of Verjus in the Wikipedia article on “Verjuice”.

We are going to concentrate on the ingredient itself and why in France it went from being a basic pantry article to a qualitative Chef’s tool.

Let’s start with the name: Verjus, which is cooler than the Anglicized ‘Verjuice’.

Second point is than not all Verjus are created equal. In the past year I have tasted some American Verjus that would wake up the dead and some European Verjus so sickly sweet that diabetics would pass out just by opening the Verjus bottle. Ok, it is an exaggeration but you get the point. A lot of people are making Verjus, but clueless about what the result should taste like, be used for, or the basic story behind Verjus.

From Basic pantry to Chef’s tool:

Verjus has been around for a long, long time … in fact a basic pantry ingredient in the Middle Ages across Europe and stretching into the Middle East. Young grapes crushed bring forth an acidic juice that is not as harsh as vinegar, but as useful. During late spring to fall the ingredients for Verjus are plentiful so it was used for salad and as a cooking ingredient. In Winter the Verjus would run out and people would switch to the more acidic vinegar.

Since wine production in France and Italy started to spike seriously, there were a lot of grapes available, and in fact one of the key ways to make your wine better is to ‘thin the grapes on the vine’ by cutting unripe clusters early.

Farmers from any part of the world are loath to just throw away even these clusters so they made Verjus … a lot of it.

So why did Verjus stop being used?

In two words, it fell victim to convenience and competition.

As wine production and quality of wine increased, so did the quantity of the more acidic cousin to Verjus, vinegar. Vinegar has a long shelf life and it got cheaper and cheaper, basically driving Verjus into a regional specialty.

Additionally lemons from the Far East were coming to Europe (brought back by Crusaders & their troops) growing all over the Mediterranean Basin. A lemon is instant acid in a self-contained package: the fruit.

The key point to understand is that Verjus and vinegar are very different products, something Chefs know.

Now this may be a case of sour grapes (pardon the pun …) but Verjus is a better ingredient to work with.

Wine Complementary:

If you are going to be serving a particularly good wine or wines with a meal, a salad dressing made with Verjus is going to be much more complimentary and not clash the way vinegar does.

Why? It has to do with the chemistry. The tartness and sourness of Verjus comes from tartaric acid, which is wine complimentary. Lemons for example the acidity comes from citric acid. Vinegar’s acidity comes from acetic acid.

Fonds de sauces:

Being a slightly sweeter liquid Verjus is just made for that Chef’s technique we read about but now you can claim as your own: deglazing a pan.

“Deglazing” is defined as “a cooking technique for removing and dissolving browned food residue from a pan to flavor sauces, soups, and gravies.” It is all about freeing flavour and Verjus is the solvent used to dissolve the aromatic elements at the bottom of the cooking dish to make a gravy. This is why sauces like these are called ‘fonds’ (French for bottom) or in English are called ‘bases’ because if you make them from scratch, they come from the ‘base of the cooking pot’.

Now you can deglaze with a wide variety of liquids but Verjus has the advantage of not overpowering what you are deglazing.

As a child I always wondered why my friends hated liver. I was not a big fan as well but did not hate it. My parents – being French – naturally deglazed the liver pan and the resulting sauce virtually eliminated the slimy aspect of cooked liver.

DIY Verjus?

The internet is full of the usual “Make your own Verjus” recipes, more concerned about how long it will last in the fridge instead of the taste profile and proper use.

A good Verjus is made quickly with a serious volume of uniformly unripe green grapes with equipment that minimizes the enemy of a good Verjus: Oxidation.

I can never discourage anyone from making their own Verjus, but work fast. Oxygen is not your friend when making Verjus. Answer a long phone call while making it yourself and your light green translucent Verjus will be brown.

Does Verjus stop at the kitchen?

Turn around and head to the bar. Verjus has been used by Mixologists as an innovative cocktail ingredient because in the same way that it compliments gravies by not competing with the cooking flavours, in a cocktail it adds without overpowering. A natural ingredient that has come back.

So bring the genius of the Middle Ages, the authenticity of wine-making terroir, from Spain to Iran, and add Verjus to your pantry.

Then you have a fundamental ingredient that Chefs use regularly because they know the benefits.